October is Black History Month; a time when we observe and reflect on important people and events in the history of the African diaspora. As part of our Black History Month celebrations, we’re honouring Andrew Watson – the first black international football player.

The following article was kindly written by Llew Walker; the author of Andrew Watson’s biography Andrew Watson, a Straggling Life: The Story of the World’s First Black International Footballer.

Football wasn’t invented; it evolved. Around 140 years ago, the game of football was beginning to take a recognisable shape. More by chance than design, those active in the game helped fashion a sport that would embrace British hearts and minds, eventually captivating every nation on the planet. Only through the luxury of hindsight can we understand how it evolved into ‘the beautiful game’, and only recently has the importance of the contribution of Andrew Watson to the game’s evolution been realised.

Football wasn’t invented; it evolved. Around 140 years ago, the game of football was beginning to take a recognisable shape. More by chance than design, those active in the game helped fashion a sport that would embrace British hearts and minds, eventually captivating every nation on the planet. Only through the luxury of hindsight can we understand how it evolved into ‘the beautiful game’, and only recently has the importance of the contribution of Andrew Watson to the game’s evolution been realised.

It probably comes as a surprise that one of the most important and influential individuals of that era was half Scottish, half Guyanian, and a resident of Liverpool for nearly thirty years!

Having played for several of the best teams in the world, Andrew Watson’s appearance on the football field for the relatively undistinguished Bootle Football Club came as a surprise to many. By the time he had arrived in the city in 1887, he had played very little football since retiring a year earlier. However, he had lost little of his ability and quickly became a crowd favourite, playing over 40 games before injury ended his season and his football career forever.

Signing Watson was a significant coup for the club. He was an international footballer, having played for Scotland three times, once as captain. He had also captained Queen’s Park, arguably the best team in the world at the time and had been the mainstay of their defence for many seasons. Watson was also a Corinthian and had famously captained the amateurs in defeats of F.A. Cup winners and top professional Northern clubs. He was a footballing celebrity. Plus, he was an amateur, which meant they wouldn’t have to pay him! Bootle was more than proud to call him one of their own.

Watson’s name is not widely known. He does not appear in many early books about the history of football. There are no statues or civic memorials to him. He is a forgotten pioneer whose influence on the early development of football stretched beyond these shores to every corner of the globe. Ironically, his absence from the beautiful game’s history is partly due to how the game evolved after he had retired.

Background

Andrew Watson was born in Demerara, in British Guiana, in 1856, to a Scottish solicitor and the daughter of a freed slave. His father brought him to England around the age of two, and he was privately educated before being sent to a boarding school in Yorkshire. At 15, he was sent to board at King’s College School, a modern and progressive institution in London. After which, as an English gentleman, he was expected to go up to Oxford or Cambridge. Instead, he chose to move to Glasgow and enter the university there. He joined a local football team called Maxwell, and after only four weeks of classes, dropped out of university, deciding that his future lay in football.

Andrew Watson was born in Demerara, in British Guiana, in 1856, to a Scottish solicitor and the daughter of a freed slave. His father brought him to England around the age of two, and he was privately educated before being sent to a boarding school in Yorkshire. At 15, he was sent to board at King’s College School, a modern and progressive institution in London. After which, as an English gentleman, he was expected to go up to Oxford or Cambridge. Instead, he chose to move to Glasgow and enter the university there. He joined a local football team called Maxwell, and after only four weeks of classes, dropped out of university, deciding that his future lay in football.

Having inherited a generous sum of money from his father, he invested in a local Glasgow business and a small but ambitious football club called Parkgrove, which had a meteoric rise in the city’s football firmament. Just as it was poised to become a leading light in Glasgow, it folded.

During the five years he played for Parkgrove, Watson perfected his talent and developed from a virtual novice to verging on the national team. Perhaps, more importantly, he had become a master of the ‘Scottish style’ of football.

After Parkgrove, he joined Queen’s Park, arguably, the best club in the world. He won four Glasgow Charity and three Scottish F.A. Cups with Queen’s Park and was elected captain and honorary secretary. Eventually, he was selected to play for Glasgow, a sign he was one of the best players in the city.

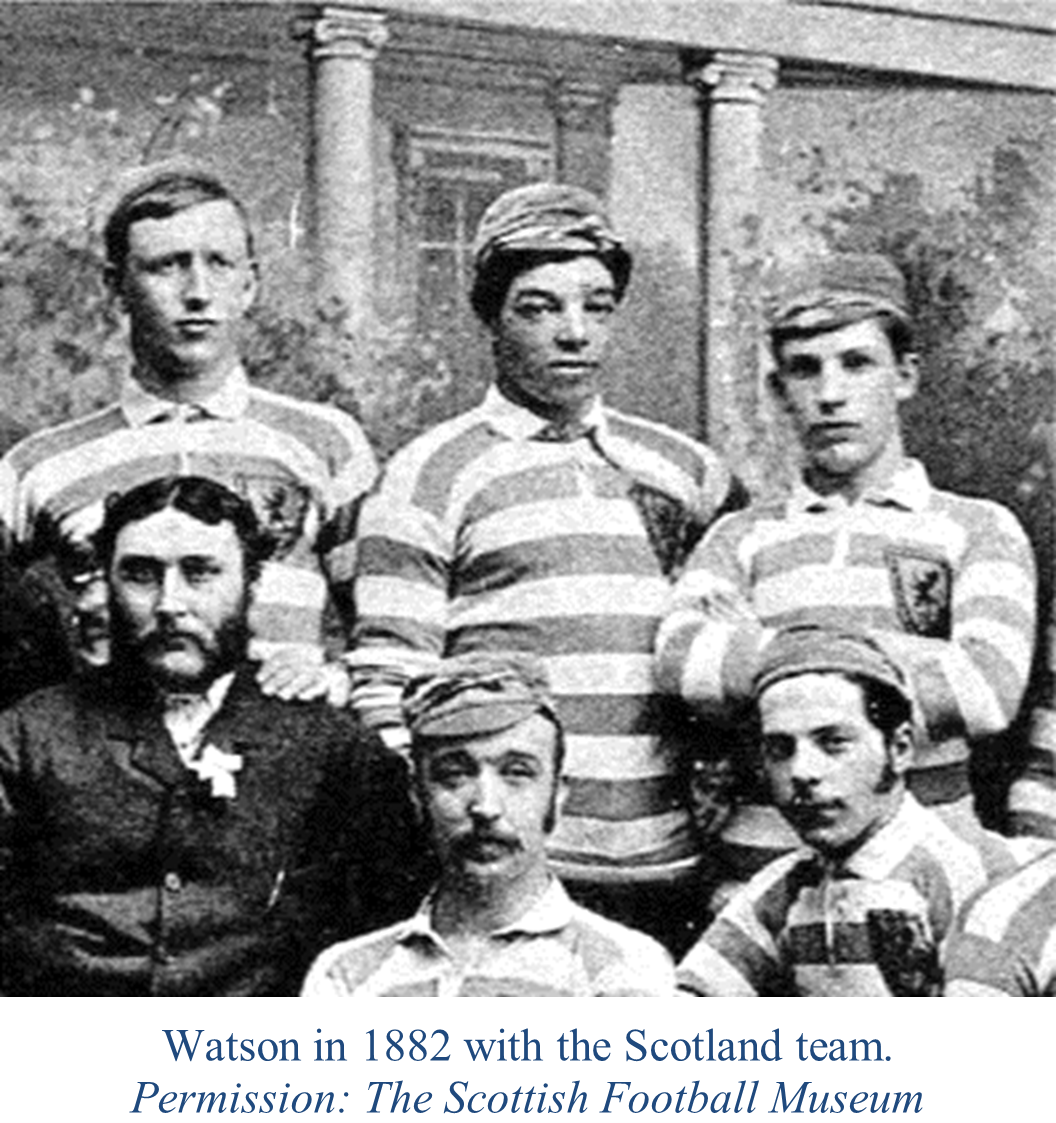

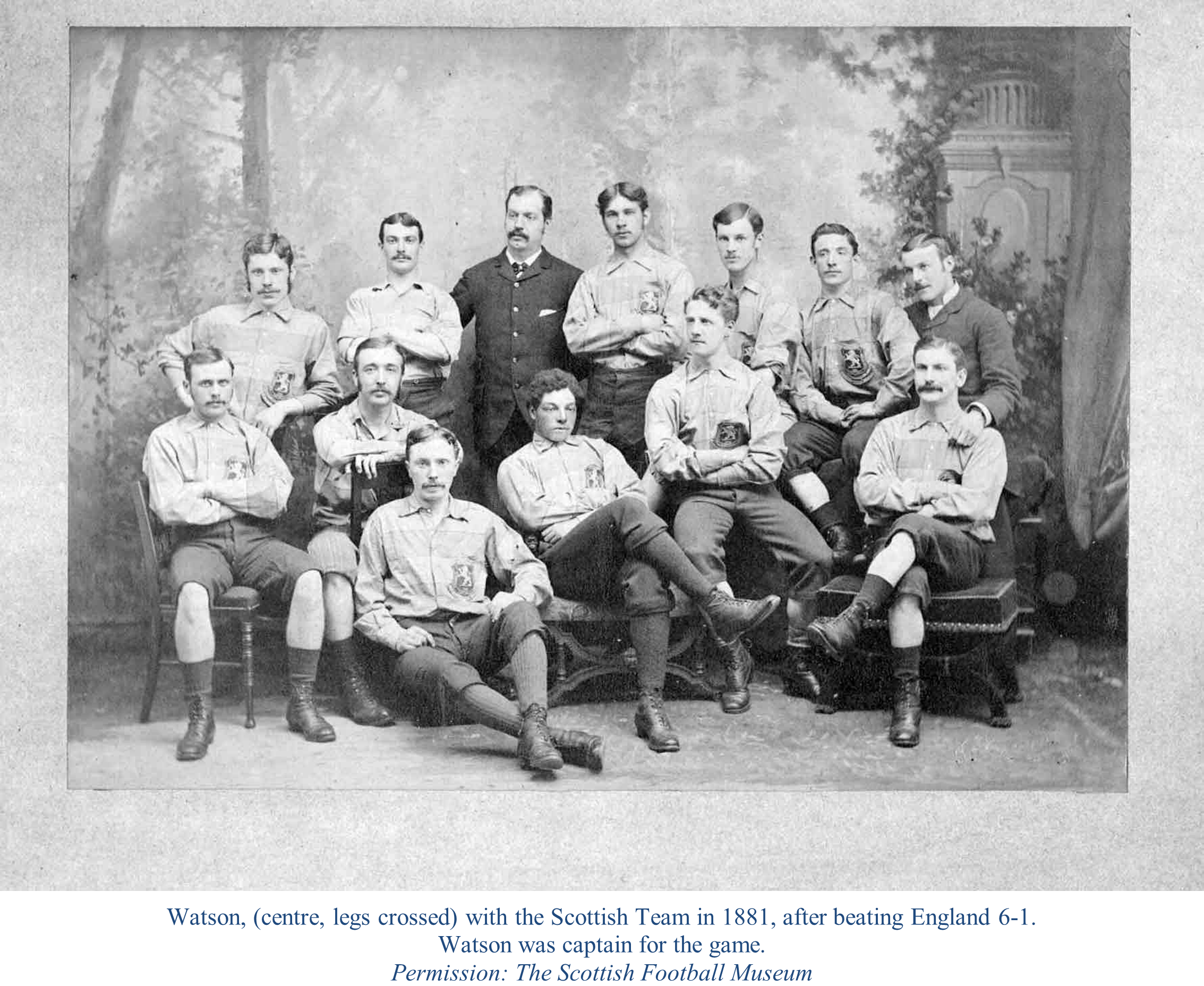

In 1881, he made his Scottish international debut as captain, defeating England at the Oval by six goals to one. (Four additional goals had been disallowed by the English referee!) This is still England’s worst ever defeat on home soil. In Glasgow, the following year, Scotland thrashed the ‘auld enemy’ again by five goals to one. This was one humiliation too many for the English F.A., and they began looking for ways to reverse the national teams’ fortunes.

Footballing Styles

Football in Scotland evolved separately from the game in England, and in international matches, the Scots outclassed the English. Even though the English players were of a very high standard, as a team, they could not match their Scottish counterparts.

The principal difference between the two distinct styles was the Scottish passing game. The English style had evolved from folk football, and a version had been adopted by English public schools as a variant of rugby. The English style was heavily influenced by the oval ball game and used a kick and rush approach, or one player charging forward with the ball at his feet surrounded by eight forwards.

At the same time, clubs in the North of England had recognised the superiority of the Scottish game. They had begun luring the best players with offers of ‘filthy lucre’ and other incentives. Northern clubs were ambitious and business-like and adhered to the economic laws of supply and demand. But the pursuit of silverware and money appalled the amateurs in the South, who believed the game should be played for pleasure, not profit. But they, too, were desperate to adopt the Scottish style.

At the same time, clubs in the North of England had recognised the superiority of the Scottish game. They had begun luring the best players with offers of ‘filthy lucre’ and other incentives. Northern clubs were ambitious and business-like and adhered to the economic laws of supply and demand. But the pursuit of silverware and money appalled the amateurs in the South, who believed the game should be played for pleasure, not profit. But they, too, were desperate to adopt the Scottish style.

The amalgamation of the Scottish and English styles is a critical moment in the evolution of football. If the English F.A. had decided not to address the problem, the game might have taken a completely different course?

The Corinthians

The English F.A. were well aware that Northern clubs were importing Scottish players. When Blackburn Rovers, with four Scots in the team, reached the final of the F.A. Cup in 1882, the writing was on the wall. For the first time, the F.A.’s crown jewel was in danger of disappearing up North, but that year, Old Etonians managed to preserve the F.A.’s dignity by winning one-nil. However, the following year, Blackburn Olympic took the Cup back to Lancashire. The F.A. faced a dilemma, not only with the international team but at club level too.

For years the backbone of the Scottish team had been drawn from one club, Queen’s Park, and many people thought this gave the Scots an advantage. In contrast, the English squad consisted of players from various clubs, and their only opportunity to play together was in international fixtures. The F.A. decided the solution was to build an English team in the Queen’s Park mould. The plan was to take the best English amateurs and play regular competitive games throughout the season against high-quality opposition. This, it was hoped, would develop a better team understanding between the players. They would learn from each other and become familiar with each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Ultimately, if successful, this team could provide the backbone to the English international squad. The plan was approved, and the Corinthian Football Club came into existence.

Meanwhile, in 1882, soon after England’s most recent defeat at the hands of the Scots at Hampden, and to Glasgow’s surprise, Andrew Watson moved to London. He was soon playing for the best English amateur clubs in the South. But unfortunately, Watson’s young wife Jessie became ill and died. She was just 22 years old. Watson’s football career was put on hold, and Corinthians played their first game without him.

The Corinthian project took a while to get going, but their star began to rise when Nicholas Lane ‘Pa’ Jackson took over the team’s management. He arranged regular fixtures against the top sides from the North of England, and Corinthians recorded some memorable victories. In 1884, Watson and the Corinthians defeated the indomitable F.A. Cup holders Blackburn Rovers by an astounding eight goals to one. The result was received with incredulity, but it announced the arrival of the Corinthians.

The Corinthian project took a while to get going, but their star began to rise when Nicholas Lane ‘Pa’ Jackson took over the team’s management. He arranged regular fixtures against the top sides from the North of England, and Corinthians recorded some memorable victories. In 1884, Watson and the Corinthians defeated the indomitable F.A. Cup holders Blackburn Rovers by an astounding eight goals to one. The result was received with incredulity, but it announced the arrival of the Corinthians.

A year later, they scored another unprecedented success in defeating the ‘invincible’ Preston North End, by three goals to two. Over the following decades, the Corinthians beat many famous professional teams, such as the 11-3 defeat of Manchester United in 1904, which remains their worst ever loss, and the 10-3 defeat of F.A. Cup holders Bury, in the same year.

The Corinthians owe their existence to the defeats England suffered at the hands of Watson’s Scotland, and after he joined them and had shared his knowledge, they developed their own ‘Corinthian style’. The national team began to see more and more Corinthians, and twice, they provided the entire English team! Corinthians eventually supplied more players to the national team than any other club.

Perhaps more importantly, the Corinthians toured the world, demonstrating the game, sharing their knowledge, and introducing the sport to countries that became footballing superpowers in the modern era. As they travelled the globe, their style was copied, and they inspired the foundation of national football associations, local clubs and cup competitions. They have been described as ‘football missionaries’ and could have had no idea that the seeds they were sowing would not only germinate but flourish. In 1910, a visit to Brazil prompted the foundation of S.C. Corinthians Paulista, who, many decades later, became World Club Cup champions.

Watson returned to Scotland after three years in London, having played for numerous top clubs. To underline his prominence as a footballer, the record of his time in the South included selection for Surrey County, London and the South of England. He returned to Glasgow and rejoined Queen’s Park, retiring in 1886. A year later, he came out of retirement and unexpectedly moved to Liverpool.

The move offered Watson a career opportunity, as well as a footballing swansong. Having recently remarried, the city provided a new beginning, a chance to raise a family and put down roots. That season saw Watson return to prominence as a footballing celebrity. He was frequently mentioned in the press and became a key player for the club.

After an injury brought his career to a close, he trained as a maritime engineer and began a decade of life at sea, traversing the Atlantic on steam liners. He stayed in Liverpool for the next 27 years, longer than he lived in London and Glasgow combined. By this time, his long absences had made him a stranger to the football world. His sea-going ended around the turn of the century, but he remained in Liverpool. Unexpectedly, around the beginning of the First World War, he left Liverpool and moved to Kew in Surrey, where he died in 1921. There were no glowing obituaries or epitaphs in the press. He was buried in Richmond Cemetery and forgotten, his grave slowly disappearing under grass and soil.

After an injury brought his career to a close, he trained as a maritime engineer and began a decade of life at sea, traversing the Atlantic on steam liners. He stayed in Liverpool for the next 27 years, longer than he lived in London and Glasgow combined. By this time, his long absences had made him a stranger to the football world. His sea-going ended around the turn of the century, but he remained in Liverpool. Unexpectedly, around the beginning of the First World War, he left Liverpool and moved to Kew in Surrey, where he died in 1921. There were no glowing obituaries or epitaphs in the press. He was buried in Richmond Cemetery and forgotten, his grave slowly disappearing under grass and soil.

The significance of Watson’s achievements is not lost on Scottish football fans who this year, 100 years after his death, set up a fundraising campaign to renovate Watson’s grave. However, his significance to the game’s evolution has yet to be fully realised.

Disappearance

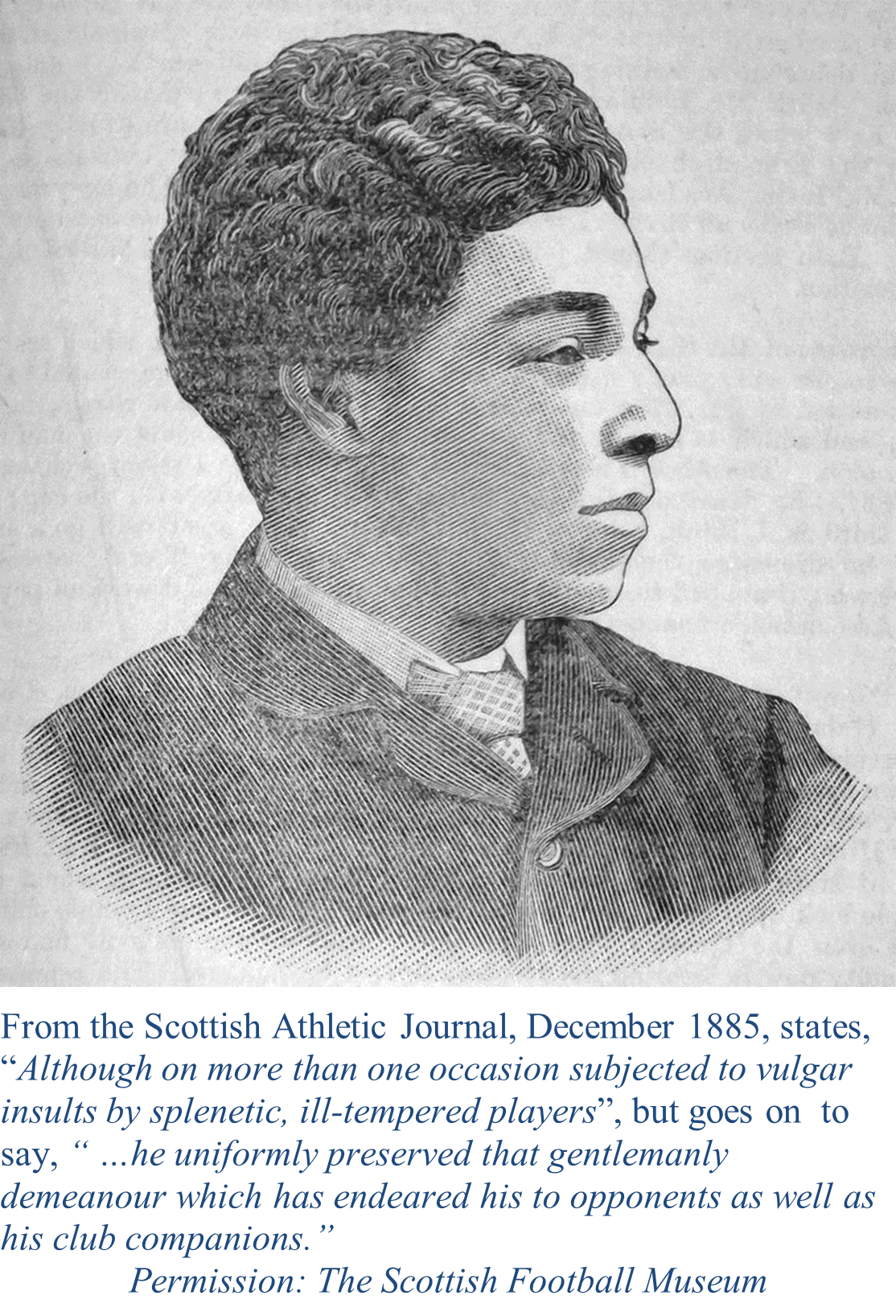

There is no evidence that Watson’s ethnicity played any part in his absence from the historical record. Racism in Victorian society was endemic, and Watson was undoubtedly exposed to bigotry throughout his life. Yet, only a few vague allusions to his ethnicity or skin colour appeared in the press.

Remarkably, most of the references focus primarily on his exceptional ability or his impeccable gentlemanly conduct on and off the pitch. Most people in England would be forgiven for not knowing Andrew Watson. Arthur Wharton or Walter Tull, two famous early Black pioneers of the beautiful game, are far more prominent. Yet Andrew Watson had preceded them both, first appearing on the football field in the 1870s. His football career spanned the most critical years in the development of the modern game. Yet, for all his achievements and celebrity at that time, he was lost to history.

Remarkably, most of the references focus primarily on his exceptional ability or his impeccable gentlemanly conduct on and off the pitch. Most people in England would be forgiven for not knowing Andrew Watson. Arthur Wharton or Walter Tull, two famous early Black pioneers of the beautiful game, are far more prominent. Yet Andrew Watson had preceded them both, first appearing on the football field in the 1870s. His football career spanned the most critical years in the development of the modern game. Yet, for all his achievements and celebrity at that time, he was lost to history.

Doubtless, few people active in football in the 1870s and 1880s considered their actions had any historical value. No one could have predicted how the game spiralled over the following decades. Even now, it’s hard to imagine that once upon a time, the only football played in Britain was played by amateur footballers who weren’t paid! But as the game’s popularity grew, so did the business that surrounded it. As more and more professionals filled the most successful teams, the amateur game slipped from prominence while professional football was propelled onward.

Similarly, the Scottish influence was forgotten, and the game became, as Julian Fellowes’ Netflix series called it, ‘The English Game’. However, it was not until the Scottish style had been fully absorbed, would the game acquire the necessary ingredients to flourish.

As the decades passed, the formative years of the birth of football became indistinct. Scholarly interest in the sport’s history began in the last few decades of the 20th century when academics and historians turned their attention to the sport and posed the question, “How did we get here?” The same question is still being asked today.

Watson’s Legacy

With the unification of the Scottish and English styles, the foundations of the modern game had been laid. As the years passed, new clubs were formed, local football associations, leagues and cup competitions were created, and the growth of association football continued to accelerate throughout Europe and worldwide.

When the definitive history of football is written, Andrew Watson will have a chapter to himself. Perhaps over the coming years, we may come to accept him as one of, if not the most influential footballers of all time. Statues and memorials may also begin to appear in Glasgow, London, Liverpool and Guyana, commemorating the extraordinary mixed heritage, English gentleman, Scottish international, Corinthian, Liverpudlian, and pioneer of a game that conquered the world!

Watson’s Achievements:

The first Black footballer to:

- play international football

- to play for Scotland

- to captain Scotland

- to win a major cup competition

- to play in the English F.A. Cup

- to officiate in the English F.A. Cup

- to be a club financier

- to hold a position as a football administrator

- to play for and captain Queen’s Park and Corinthians

- to play for and captain Glasgow

- to play for and captain Surrey and West Surrey County

For more information about Scottish Football History:

https://www.scottishsporthistory.com

https://www.scotsfootballworldwide.scot

Posted on 27 September 2021 under General news